Thomas Starr King

Namesake & Traditions

Learn more about our namesake, Rev. Thomas Starr King, as well as some of our traditional practices.

Jump to a topic:

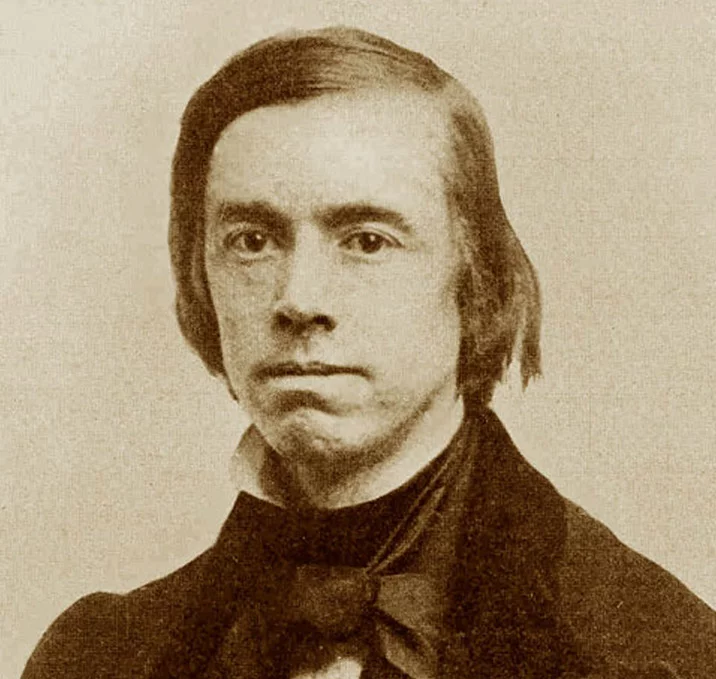

Rev. Thomas Starr King

Thomas Starr King was born in New York City in 1824 to Rev. Thomas Farrington King, a Universalist minister, and Susan Starr King. When he became the sole supporter of his family at age 15, Starr King embarked on a program of self-study for the ministry. Five years later, he took over his father’s former pulpit at the Charlestown Universalist Church in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

In 1849 he was appointed pastor of the Hollis Street Church in Boston, where he became one of the most famous preachers in New England. He preached there for 11 years before accepting a call from the First Unitarian Church of San Francisco, California in 1860. Starr King moved to California because he felt like his skills as a minister and preacher were needed more there than in Boston, as there were many Unitarian ministers in New England at the time, but few in the west. As it turned out, Starr King had great influence on California politics during the remainder of his life.

During the Civil War, California had to decide two things – whether to stay in the United States and whether to be a slave state or free state. Starr King was an excellent and convincing preacher, and he spoke throughout California, continuously, in favor of California staying in the United States and to be a free state – he was successful on both issues. Also, Starr King helped found the American Sanitary Commission, which was the original American Red Cross. He became exhausted and sick from preaching non-stop, and he died in 1864. His sarcophagus lies outside of the First Unitarian Universalist Society of San Francisco.

When Thomas Starr King first walked to the pulpit of the San Francisco Unitarian Church in 1860, the eyes of the congregation turned to this small, frail man. Many asked, “Could this youthful person with his beardless, boyish face be the celebrated preacher from Boston?”

King laughed. “Though I weigh only 120 pounds,” he said, “when I’m mad, I weigh a ton.”

That fiery passion would be King’s stock in trade during his years in California, from 1860 to 1864. Abraham Lincoln said he believed the Rev. Thomas Starr King was the person most responsible for keeping California in the Union during the early days of the Civil War.

King’s reputation as a noted orator had led the San Francisco congregation to ask him to come west, with little hope he would agree. During his 11 years as minister of Boston’s Hollis Street Unitarian Church, King increased the congregation to five times its original size and pulled the church out of bankruptcy. Ralph Waldo Emerson, noted essayist and poet, said after hearing one of King’s sermons, “That is preaching!” Churches in Chicago and Brooklyn sought King as their minister, but this popular Boston pastor rejected them. San Francisco, he decided, offered the greatest challenge.

California in Crisis

California was headed into a crisis. At hand was a showdown between the free states of the Union and the slave states. California’s governor and most members of the state legislature were sympathetic to the Confederacy. The only effective voice against slavery, Sen. David C. Broderick, had been killed in a duel the year before.

The San Francisco congregation’s initial disappointment about King’s slender, boyish appearance soon gave way to wonder, then delight at his rich, golden voice. Not only did King establish his reputation as an orator and preacher that first Sunday in San Francisco, but the news soon spread statewide, attracting worshipers from Stockton and Sacramento.

Less than a month after King arrived in California, the Republican National Convention met in Chicago and nominated Abraham Lincoln as its presidential candidate. In the following election, Lincoln carried California by only 711 votes.

Southern states soon abandoned the Union. The crucial question on the minds of many Americans was: Would California join them and deliver the state’s immense natural resources into the hands of Confederate President Jefferson Davis? Support for secession was strong in southern California, where the Confederate flag had flown over Los Angeles’s main plaza on the Fourth of July.

At that time the U.S. Congress was so convinced of a secessionist plot that it required Easterners to secure passports for travel to California. Justifying Congress’ fears was a secret paramilitary California secessionist organization of about 16,000 members, called the Knights of the Golden Circle.

On George Washington’s birthday in 1861, King fired an opening salvo in support of his country. He spoke for two hours to over a thousand people about how they should remember Washington by preserving the Union.

Pledging California

“I pitched into Secession, Concession and (John C.) Calhoun (former U.S. vice president), right and left, and made the Southerners applaud,” King recalled. “I pledged California to a Northern Republic and to a flag that should have no treacherous threads of cotton in its warp, and the audience came down in thunder. At the close it was announced that I would repeat it the next night, and they gave me three rounds of cheers.”

Speaking up and down the state, King visited rugged mining camps and said he never knew the exhilaration of public oratory until he faced a front row of men armed with Bowie knives and revolvers. His friend, Edward Everett Hale, who made a similar contribution to saving the Union through his moving story, “The Man Without a Country,” said, “Starr King was an orator no one could silence and no one could answer.”

King covered his pulpit with an American flag and ended all his sermons with “God bless the president of the United States and all who serve with him the cause of a common country.” At one mass rally in San Francisco, 40,000 turned out to hear him speak. A group of Americans living in Victoria, B.C., sent him $1,000 for his work to preserve the Union. King was beginning to turn the tide.

In 1861, he threw himself into the gubernatorial campaign of his parishioner, Leland Stanford. King and author Bret Harte often accompanied Stanford on speaking tours. Stanford won an overwhelming victory and King sighed with relief.

“What a privilege it is to be an American!” he said. “What a year to live in! Worth all other times ever known in our history or any other!”

A New Front

The battle to keep California in the Union won, King now turned to the needs of its soldiers. The Union Army lacked provisions and medical personnel. Much of its food was rotting because of spoiled goods sold to the Army by war profiteers. Soldiers lacked sheets and blankets, and disease took a greater toll than Confederate bullets.

In response, the Rev. H.W. Bellows of New York organized the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a forerunner of the American Red Cross. Starr King immediately pitched in to help. Out of $4.8 million the commission raised throughout the U.S., King raised $1.25 million in California. About $200,000 came from San Francisco, a figure all the more impressive because of a series of natural disasters in the state, including a massive flood that turned the Sacramento-San Joaquín Valley into a vast lake and a drought that wiped out the wheat crop.

Now King found himself raising funds for flood and drought relief. He also carved out time to work for the rights of San Francisco’s African Americans and Chinese.

“We know,” said Edward Everett Hale of King, “that here is a heart as large as the world, so that you can not make it understand that it should hold back from any service to be rendered to any human being.”

Because of King’s success in patriotic and charitable causes, powerful friends encouraged him to run for the U.S. Senate. But he refused, saying he feared it would lead to political compromise and impair his ability to speak forthrightly. “I would rather,” he said, “swim to Australia.”

Relaxation and joy came from exploring California’s wilderness. He was among the first 100 Euro-Americans to visit Lake Tahoe. To him, the blue lake and green pines seemed in harmony with the deepest religion of the Bible.

Yosemite Valley and its giant trees gave him special delight. Back in New England he enjoyed exploring the White Hills of New Hampshire and wrote a book about them, “The White Hills—Their Legend, Landscape and Poetry.”

On entering California’s great valley, he said, “The Ninth Symphony (by Beethoven) is the Yosemite of music! Great is granite and the Yosemite is its prophet!” He climbed above the falls, attracted by a dome of granite towering 13,600 feet over the valley. Today it bears his name, Mt. Starr King.

San Francisco Church

Despite his many commitments in California, King always put his church first. When he arrived in San Francisco in 1860, the congregation struggled with a $30,000 debt. Within the first year, King managed to raise the funds to pay it off. Now he turned his attention to an expanding congregation in a too-small church. In October 1862, he set an $80,000 fundraising goal. By December of that year, the cornerstone of a new church was laid. In January 1864, King and his congregation celebrated the completion of the new building at 133 Geary street, adjacent to present-day Union Square. (The congregation eventually relocated its church again in 1889 to the corner of Franklin and Starr King streets in San Francisco, where the First Unitarian Universalist Society church stands today.)

His congregation now prosperous, the Union Army driving to victory and the Sanitary Commission on solid footing, King decided to take a much-needed sabbatical. He planned to rest, travel and write a book about the Sierras.

Declining Health

But King’s Herculean efforts had taken a toll. Only devotion to what he considered God’s will and “being mad” kept him going. On Feb. 28, 1864, he came down with diphtheria, then pneumonia. A few days later his doctor told him he had only a half-hour to live. King glanced at a calendar.

“Today is the fourth of March,” he said. “Sad news will go over the wire today.”

He dictated his will and turned to his wife. “Do not weep for me,” he said. “I know it is all right. I wish I could make you feel so, I wish I could describe my feelings. It is strange. I see all the privileges and greatness of the future. It already looks grand, beautiful. Tell them I went lovingly, trustfully, peacefully.”

A State Mourns

Across San Francisco, flags dropped to half-mast. The state legislature in Sacramento adjourned for three days of mourning after passing a resolution stating that King had been a “tower of strength to the cause of his country.”

As King lay in state, wrapped in an American flag, a military honor guard stood by his casket. Twenty thousand people came to his church to pay tribute. Cannons boomed a memorial tribute and Bret Harte composed a eulogy, “Relieving Guard.”

A Star? There’s nothing strange in that.

No, nothing; but above the thicket

Somehow it seemed to me that God

Somewhere had just relieved a picket.

King’s body was buried in the front lawn of his newly completed church, where it remains today.

Tribute

In 1913, the state legislature voted Thomas Starr King and Father Junipero Serra, the Catholic missionary, as California’s two greatest heroes and appropriated funds for King’s statue at the U.S. Capitol. In the 1960s, the state designated King’s church and tomb as a historical monument.

In addition to Yosemite’s granite mountain, one of the great trees within the park that King admired was also given his name. Another mountain in the White Hills of New Hampshire is known as Mt. Starr King, and several schools throughout California bear his name.

In 1941, the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry changed its name to Starr King School for the Ministry to honor a man of eloquence, commitment and vision.

Adapted from an article written by William H. Wingfield for Real West Magazine, August 1972.

The San Francisco Chronicle featured Thomas Starr King in an article “Starr King rallied SF for a cause” in 2013.

Crossing the Threshold

Thresholds represent a liminal space – between one space and another. At Starr King, we honor this change. Moving through the liminal space of life and into one that includes the space to study faith traditions is a special one. As part of matriculation, we welcome our new students in through a long tradition of Crossing the Threshold at which time we celebrate the call to spiritual and religious leadership and welcome in our students.

Our Threshold is crafted in conjunction with our Center for Multi-Religious Studies to create a welcoming environment for all in which we can celebrate the achievement of coming to seminary and marking the change that is happening and will continue to happen in each student’s life as they grow and change. We use both time-honored traditions and new traditions to create a truly multi-religious experience to mark this special occasion.

Chalice Lighting

The flaming chalice was created by Hans Deutsch in 1941, during World War II when it was commissioned by the Unitarian Service Committee (USC). In 1976, the Unitarian Universalist Association included this in their title page of the directory. The ritual of lighting a chalice became part of worship in the last 30 years, giving credit to both ancient traditions and new.

The lighting of a chalice is a tradition that we use to honor the roots of our organization in the Unitarian Universalist tradition, and as a gentle reminder to us of our call to service in faith. The words we speak when we light the chalice were written by the Starr King Worship Committee and Emerita President Rev. Rebecca Parker.

“With the kindling of this flame, we reaffirm our commitment to accept life’s gifts with grace and gratitude and to use them to bless the world in the Spirit of Love.”

Red and White Candles

The lighting of the red and white candles are a tradition brought to us by Emerita President Rev. Rebecca Parker to accompany the chalice lighting. The white candle is lit to symbolize the symbolize violence, suffering, and death, and to serve as a reminder that we gather in times of war. The red candle symbolizes the abiding reality of love and the shared work to restore the human community and the Earth to wholeness and harmony – and to serve as a reminder that this is the work that we are called to do.

Sand Dollar

Rev. Dr. Robert “Bob” Kimball, previous SKSM President, Professor, and Dean chose the sand dollar as a symbol for the school as a reminder of walking along the beach – a liminal space between the sea and the shore. These liminal spaces are areas of transformation and give way to change, to growth, to opportunity. Each beach walker has their own responses, their own discoveries, and each is drawn to different things – just like an education at Starr King. Every sand dollar is unique – some stained by mud or seaweed, some weathered by the ocean, but every one has a story to tell and a purpose.